Frank Purdy Williams

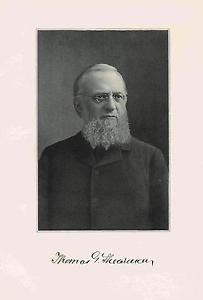

Frank P. Williams Thomas G. Shearman

Frank Williams was a friend of Henry George in New York. Frank dedicated a book to George, attended dinner with HG, corresponded with him. Frank also knew Thomas Shearman. I presume he met him personally. Williams and Shearman were hanging around HG during the same period from 1880 until HG’s death in 1897. Both lived in Brooklyn before the Brooklyn Bridge was completed. This means that they had ample opportunity to observe each other during a time when Brooklyn was more of an isolated community. Williams and Shearman had an interesting exchange in the New York Times letters page just a days before George died of an apparent stroke.

After the full letters, I’ll make my arguments with support from excerpts and other background info.

The first letter is from F.P. Williams, Montclair, New Jersey.

From the New York Times of October 25, 1897:

MR. GEORGE AND HIS FRIENDS

Montclair Man Thinks the Single Taxer Would make a Bad Mayor

To the Editor of The New York Times:

As some of your readers may or uncertain as to whether Seth Low or Henry

George ought to have their votes, I would like the privilege of saying a

few words in your columns that may help to clear up that uncertainty.

Intimately associated with Tom L. Johnson as Mr. George is, I do not

thing that he ought to be elected Mayor. For my part, I would far

rather cast a vote fro Seth Low the inflexible than for the good-natured

friend of an arch-monopolist, who says that he believes in a better

social order than the present and who at the same time declares that he

means to work the existing social order for all that it is worth.

Everybody who has passed out of childhood knows that the President of

the Nassau Railroad would not be the friend of the Mayor of Greater New

York for nothing.

“But,” it will be said, “Mr. George declares that he is no man’s man.”

I suppose that he does not fully believe just what he declares; but Mr.

George’s greatness of intellect does not consist in an ability to

discern between true and false friends when political matters are at

stake – of that I am certain.

I was intimately associated with Mr. George for years. During his

campaign of 1886 he selected for one of his chief managers a man whom he

had already chosen for a bosom friend – a man who in his whole bearing

showed himself to be a thoroughgoing self-seeker, and worse; a man,

moreover, who, by common report, had been guilty of bribery, or

attempted bribery, of public officials. This man’s character was

understood by everybody except Mr. George, whose eyes were not opened

until one day when he received a treacherous stab from the man he had so

blindly trusted. I remember distinctly Mr. George’s mournful

astonishment; I remember distinctly a letter that I wrote to him at that

time, saying that the only wonder was that he had been so long finding

out the man’s true character, and I remember distinctly Mr. George’s

reply, that he wished I had informed him before.

History repeats itself; what has once happened can happen again. It

would be a dark day, I fear, the day that would see New York City

handing the reins of government to the close friend of Tom L. Johnson.

What satisfaction would it be to me, Mr. Editor, or to any other owner

of property in Greater New York, to be told by Mayor Henry George after

the city entrusted to his care had been so enmeshed in monopoly’s deadly

coil that even had he begun to see the danger – what satisfaction would

it be to use then, I ask, to be told by Mayor Henry George that he

wished he had been notified of Tom L. Johnson’s real character before?

I do not mean to say one word in disparagement of Mr. George’s

character. No man realizes more fully that I his mighty achievements;

few men have done more that I to win converts to his philosophy. But I

truly believe that even the most unswerving single taxers will, if they

think this matter over carefully, come to the conclusion that Mr.

George, mighty as he is in the domain of political economy, is not at

all a man to be entrusted with the Mayoralty of Greater New York.

F. P. Williams

Montclair, NJ Oct. 21, 1897

The response from Shearman, penned the same day Williams’ letter was published:

NY Times Oct 27, 1897:

MR. GEORGE NOT A SOCIALIST

So Writes Thomas G. Shearman Regarding the Single Taxer – Tom L. Johnson Defended

To the Editor of the New York Times:

It is with regret that I have notice the space you have given to attacks upon Henry

George and Tom L. Johnson by pretended labor leaders and New Jersey cranks. Not a

single criticism of either has proceeded from any genuine workingman; while, as to

the gentleman who has last been honored with prominence in your columns on this

theme, his own book, which he has vainly struggled to bring to public attention,

shows that he believes all government to be wicked and think that it was a fearful

mistake that the Union was not allowed to be dissolved entirely in 1861.

Such criticism, however, furnishes merely the occasion for the present letter.

There has been a large amount of more sincere criticism, upon both Mr. George and

Mr. Johnson, from other quarters. On the one hand, far too much has been said by

respectable newspapers and respectable men as to Mr. George’s supposed Anarchistic

and Socialistic tendencies, while on the other hand gross injustice has been done

to Mr. Johnson on the assumption that the owner of steel mills cannot possibly be a

sincere free trader and the owner of street railways cannot be a sincere

anti-monopolist.

Mr. Johnson is of a distinguished type of men, so rare that people of low and

sordid minds cannot believe in their existence. Not only is he the only

manufacturer or monopolist in the United States who ever went to Congress without

voting and clamoring for the passage of bills which would put money directly into

his own pocket, but he has uniformly voted for and urged measures which would

directly tend to diminish his personal profits. The standard of political life

among us is, unhappily, so low and venal, even among the most highly respectable

and religious classes, that no Congressman, however high-toned or religious, with

the single exception of Mr. Johnson, has ever taken this manly course within the

memory of the present generation. Before the war there were slaveholders who

ardently supported every measure for the emancipation of their slaves without

compensation to themselves. A very few of these obtained entrance into public

life, and perhaps it is because Mr. Johnson was born in Kentucky – a State which

furnished more of such men to public life than any other – that he has retained

some of the noble traditions of Cassius M. Clay and Robert J. Breckinridge. It is

lamentable that the groveling instincts of so many of our Northern people should be

unable to comprehend even the existence of a man among us who is worthy to stand

with these heroes of a past time.

With regard to Mr. George, the misunderstanding of his motives and political

theories is simply ludicrous. Even Abram S., Hewitt seems to be filled with the

delusion that Mr. George wants to seize and divide up private property; while many

editors, who aught to know better, constantly speak of him as a Socialist. Mr.

George is as far removed from being a Socialist as Mr. Low or Mr. Tracy. In fact,

he is less of a Socialist than either of those gentlemen because both of them are

in favor of some kind of protectionism, which is necessarily Socialism, only for

the benefit of the rich.

It is good political tactics for Tammany Hall to represent Mr. George as a

Socialist, but is is the greatest folly for any friends of Seth Low to do so. If

Henry George does not receive, at the very least, 75,000 votes, it seems to be

impossible that Seth Low could be elected. At the very least, three-fourths of all

Mr. George’s votes will be drawn from those who would other wise voted for the

Tammany ticket. If Mr. George receives 100,000 Mr. Low will be elected. If he

does not receive more than 50,000 votes, Mr. Low will be defeated. Mr. George is

not running for the purpose of electing Mr. Low; but Mr. Low’s supporters ought to

use some common sense in dealing with the problem before them. The Citizens’

county ticket stands no earthly chance of success without the hearty support of Mr.

George’s followers.

The citizens of New York are therefore confronted with one or the other of two

results. Either Tammany will acquire absolute control of this great city for the

next four years, or else on the morning after election it will be telegraphed all

over the world that Henry George has received about 100,000 votes in this city. If

the present foolish misrepresentation of Mr. George’s theories and attitude is

continued, this result will create universal, and yet entirely causeless, alarm

among business men everywhere.

It is therefore well worth while to make the fact clearly understood that, even if

Henry George were elected Mayor of New York, and even if he had ten times the power

which he would have if elected, the whole tendency of his administration would be

to secure to every honest man all rights to property which he honestly owned. As

mayor of New York his duties could only be executive, and his bitterest enemies

concede that Mr. George is, and would be in any such office, a thoroughly honest,

upright, and incorruptible public servant. I shall not vote for him, because I

sincerely believe that Seth Low is equally honest and incorruptible, and that by

reason of long experience and study in the direction of executive work he will make

a more efficient Mayor than would Mr. George. But it would be impossible to find a

purer man in public and private life, or one who might more safely be trusted with

respect to his own action and the action of all others, so far as he could control

them, than is Mr. George.

But it will be said that the ideas of Mr. George, in matters not executive but

purely legislative, are so dangerous that a large vote for him will indicate bad

future results. This question proceeds upon an entire misapprehension of both the

man and his theories. If his theories were carried out to the fullest extent,

which is possible in the nature of things, every man who owns a house, a factory, a

mill or shop, machinery merchandise, bonds, notes, bank stock, bank deposits,

horses, cattle, fruit trees, and, in short, everything which is made by the human

hand or grows from the soil, will be the absolute owner of these things, free from

taxes, and without the possibility of their ever being taken from him by taxation.

Whether this is desirable or not it is not necessary just now to inquire. It is

sufficient that a man who holds such views is the very opposite of a Socialist or

of an enemy to property. These ideas may be, as is often said, quite

impracticable; but it is certain, in the first place, that Mr. George would not, if

he had the power, adopt any substitute for these impracticable ideas, which would

be injurious to this kind of property, and, in the second place, that, as Mayor of

New York, he could only use his moral influence in favor of such ideas.

Meanwhile, the vote which may be cast for Mr. George will, in any event, be so

large that it is of serious importance that no one should be misled into the belief

that this vote represents, in any sense, either Socialism or Anarchy, or anything

resembling either

Thomas G. Shearman

New York, Oct. 25, 1897

OK. Now to what I’m trying to do with this stuff. Teasing out the characters of Shearman, Williams, and George.

I want to concentrate on the first paragraph of Shearman’s letter:

“It is with regret that I have notice the space you have given to attacks upon Henry

George and Tom L. Johnson by pretended labor leaders and New Jersey cranks. Not a

single criticism of either has proceeded from any genuine workingman; while, as to

the gentleman who has last been honored with prominence in your columns on this

theme, his own book, which he has vainly struggled to bring to public attention,

shows that he believes all government to be wicked and think that it was a fearful

mistake that the Union was not allowed to be dissolved entirely in 1861.”

And concentrate on this part of Williams’ letter:

“I was intimately associated with Mr. George for years. During his

campaign of 1886 he selected for one of his chief managers a man whom he

had already chosen for a bosom friend – a man who in his whole bearing

showed himself to be a thoroughgoing self-seeker, and worse; a man,

moreover, who, by common report, had been guilty of bribery, or

attempted bribery, of public officials. This man’s character was

understood by everybody except Mr. George, whose eyes were not opened

until one day when he received a treacherous stab from the man he had so

blindly trusted. I remember distinctly Mr. George’s mournful

astonishment; I remember distinctly a letter that I wrote to him at that

time, saying that the only wonder was that he had been so long finding

out the man’s true character, and I remember distinctly Mr. George’s

reply, that he wished I had informed him before.”

Shearman takes a snipe at Frank Williams’ book. I’m not sure which one he refers to. Williams is recognized today as one of first authors of alternate history novels. One such is on Google: https://books.google.com/books?id=qQZCAQAAMAAJ&pg

Check out the front leaf bio that mentions Henry George. Another of Williams’ books is dedicated to Henry George.

Just cheap shots from the dirty lawyer, Shearman.

I don’t know what the “treacherous stab” was. I do believe Henry George must have known who Thomas Shearman was well before they met in New York in 1880. Shearman was involved in some very shady stuff going back when he was part of the legal team for the Erie Railroad owned by Jay Gould and Jim Fisk. This was when Shearman was involved in paying off Judge Barnard in NYC to write crazy injunctions to stop an Erie shareholder meeting in Albany. This included injunctions to arrest shareholders and throw them in jail. Nice stuff like that. The judge was eventually impeached and the outrage against the lawyers involved led to the creation of the New York Bar Association and its standards of ethics for lawyers. This was national news. The next case was the Gold Ring of 1869 when Gould and his lawyers ran up the price of gold and ruined many investors. Again, national news. Then in 1875 came the scandal of the century, the adultery case of Reverend Henry Ward Beecher and a married woman of his church. Shearman defended Beecher in the drawn out courtroom drama that was carried daily in many paper across the country.

All of these events happened while Henry George was in the newspaper business. He commented on them in his own papers and books. George knew damn well Shearman was no honorable gentleman. The truth is, Shearman brought money and connections to George to help sell his books, finance his mayoral campaign, and bankroll his newspaper, The Standard. Shearman took advantage of his position as patron to direct George’s writings in the direction of British Free Trade and away from Monetary Reform and the rights of Labor.